The Voice of the People: Public Comment PROCESS and Participation Curtailed

By Elaine Cimino 11/16/18

Changing the rules in midstream is just what Congress did when it passed HR 348, the “Responsibly And Professionally Invigorating Development”, or “RAPID Act”, in 2015. The Act curtailed public comment periods to 30 days and obstructed public participation. Over the past 10 years, the National Environmental Protection Act (NEPA) has been under siege by the Chamber of Commerce lobbyists and others, who have succeeded in reframing public opposition as “NIMBYism” (Not In My Back Yard) and common sense regulations as “job killers”. By significantly reducing the public comment period, the Act limits the ability of the public and elected officials to make informed decisions. Many local communities are already reeling from the health and safety impacts caused by these widespread deregulations. The refrain heard across the country is ”this sounds a lot more like steamrolling than “streamlining.” So, it’s time to start talking facts on the threat to public participation and the right to healthy environments and public safety as a human right.

AT THE FEDERAL LEVEL

In the recent quarterly BLM oil and gas Lease Sales, the public comment periods were shortened to 10 days, with fewer public meetings. It was also reported that BLM even lost public comments:

Ben Goldfarb writes in an Audubon article, “agencies have discretion over which feedback to heed, they also have considerable latitude in

establishing the duration of comment periods. According to federal guidelines, comment periods may be as brief as 30 days, or for particularly complex rules may stretch 180 days or more. When the Obama Administration proposed a rule intended to protect water supplies from fracking-related pollution in 2015, for instance, Interior granted a 210-day comment period.”

establishing the duration of comment periods. According to federal guidelines, comment periods may be as brief as 30 days, or for particularly complex rules may stretch 180 days or more. When the Obama Administration proposed a rule intended to protect water supplies from fracking-related pollution in 2015, for instance, Interior granted a 210-day comment period.”

‘Under Trump, comment windows have seemingly trended shorter. Look, for instance, to the San Juan Basin, the vast geologic hollow that stretches from Durango, Colorado, to Gallup, New Mexico. The giant bowl is one of America’s most intensively drilled regions, perforated by more than 40,000 oil and gas wells—approximately five per square mile. Guided by a 2010 Obama Administration directive, the federal Bureau of Land Management (BLM), the wing of the Interior Department that manages the basin’s public lands, had been selling a fresh batch of drilling leases to energy companies once a year. On January 31, 2018, the Trump Administration ordered BLM’s field offices to hold quarterly sales. Overnight, the potential pace of leasing in the San Juans and other regions quadrupled. What’s more, the new directive gave people just 10 days to protest after a sale was announced. “We suggest putting the BLM leasing webpage on your ‘favorites,’” one agency spokesperson told the Durango Herald.

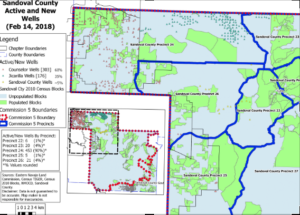

Figure 1 Active Oil and Gas Wells in Sandoval County as of Feb 2018

Figure 1 Active Oil and Gas Wells in Sandoval County as of Feb 2018

In August 2017, Zinke instated a new order setting yearlong deadlines and 300-page caps on NEPA-required Environmental Impact Statements for projects like oil and gas leasing plans. “Shorter review time periods means fewer days for public comment, fewer public meetings, fewer opportunities to reach out,” Ani Kame’euni, the director of legislation and policy at the National Parks Conservation Association, told the Moab Times when the order was issued.”

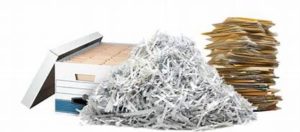

Along with the issues on Public Comments, there is the issue of the destruction of the public record in what looks like systemic racism being played out at the National Archives. A concerned archivist alerted social media to the “very disturbing action happening in the National Archives world that may severely impact research, especially historical and scientific research.” The Dept. of Interior is asking for permission to destroy records about oil and gas leases, mining, dams, wells, timber sales, marine conservation, fishing, endangered species, non-endangered species, critical habitats, land acquisition, and lots more. Records from every agency within the Interior Department, including the Bureau of Land Management, National Park Service, US Fish & Wildlife Service, US Geological Survey, Bureau of Safety and Environmental Enforcement, Bureau of Indian Affairs, and others are at risk. This is also a document on the mistreatment of Native Americans. This is all content that would normally go to NARA for collection and preservation. This is disturbing; this administration is basically just destroying records so they’ll never be accessible.

There’s an NOV. 26th deadline for comment to NARA:

- request.schedule@nara.gov

- fax: 301-837-3698

- NARA (ACRA),

- 8601 Adelphi Road, College Park MD, 20740-6001.

- (Be sure to say that you’re referring to DAA-0048-2015-0003.)

- Please forward to your networks and researchers who may be affected

More information: https://altgov2.org/doi-records-destruction/

NARA’s appraisal memo https://altgov2.org/wp-content/uploads/DAA-0048-2015-0003_Appraisal_Memo.pdf - NEW PDF: Department of the Interior: Request for Records Disposition Authority [correct version]

- NEW PDF: Department of the Interior: Crosswalk (i.e., detailed guide to the documents) [correct version]

- PDF: National Archives & Records Administration: Appraisal Memo

The incorrect version was sent out, so the deadline was extended to Nov. 26th for comment, Federal agencies don’t keep most of their records forever. At some point, they’re legally allowed to destroy the majority of them.

But when? And which records? That’s up to the agency and the National Archives (with some input from the public, at least in theory).

In an overlooked process that’s been going on for decades, agencies create a “Request for Records Disposition Authority” that gives details about the documents, then proposes when they can be destroyed (e.g., three years after the end of the fiscal year, 50 years after they’re no longer needed, etc.). Occasionally, agencies propose keeping some documents permanently, which means eventually transferring them to the National Archives.

The National Archives & Records Administration (NARA) then “appraises” the agency’s Request for Records Disposition Authority, almost always giving the green light. Around this point, the agency’s request and NARA’s appraisal are announced in the Federal Register. They are not published in the Register, nor are they posted to the Register website (including Regulations.gov). Their existence is simply noted.

The National Archives & Records Administration (NARA) then “appraises” the agency’s Request for Records Disposition Authority, almost always giving the green light. Around this point, the agency’s request and NARA’s appraisal are announced in the Federal Register. They are not published in the Register, nor are they posted to the Register website (including Regulations.gov). Their existence is simply noted.

It’s then up to you to write NARA and ask for copies of the request and appraisal. Once you get them, you have 30 days to make a public comment to NARA. Then the process continues, usually resulting in NARA giving final approval to the agency’s wishes.

This is an extremely important process. This issue affects transparency, accountability, research, the historical record, and the Freedom of Information Act (you can’t successfully request documents that have been destroyed). Yet it’s been happening in the shadows for decades. Public Documents deserve transparency.

In New Mexico, on the western public, state and private lands, it also obstructs our ability to make evidence-based policy decisions and further undermines the NEPA process. The decision of what to archive and what is destroyed is serious, especially when it affects cultural entities, endangered species etc. The public is best served by trained clerks that know how to organize archival materials.

As George Orwell rightly states in the dystopian nightmare book, ‘1984’, “Every record has been destroyed  or falsified, every book was rewritten, every picture has been repainted, every statue and street building has been renamed, every date has been altered. And the process is continuing day-by-day and minute-by-minute. History has stopped. Nothing exists except an endless present in which the Party is always right.” A totalitarian regime appears to be on the rise in the United States, impacting public participation, and destroying the public record and government transparency.

or falsified, every book was rewritten, every picture has been repainted, every statue and street building has been renamed, every date has been altered. And the process is continuing day-by-day and minute-by-minute. History has stopped. Nothing exists except an endless present in which the Party is always right.” A totalitarian regime appears to be on the rise in the United States, impacting public participation, and destroying the public record and government transparency.

AT THE STATE LEVEL

At the state levels, several states enacted a series of measures to streamline and coordinate time limits on the permitting process. In California, the state required automatic approval of a project if the streamline-shortened timeframes are not met despite the concerns brought forward.

The State of New Mexico passed HB 58 in the 2018 legislative session that also streamlines public comment for all state agencies from 60 days to 30 days, with some public commenting periods curtailed to 15 days. The Attorney General responded with a “Concise Explanatory Statement” on default procedures for the agencies and those councils, boards, and commissions who don’t have procedures in place, to submit findings of evidence-based policy decisions. Now a state agency must give findings, a reason to reject and/or accept the proposed project or legislation on a public comment submitted. Not all comments fall under one umbrella. On a quasi-legislative issue where a decision would impact citizens who are allowed a right to address grievances to the district court; and in cases at the local level, agencies, boards, county commissions, these entities must give findings on public comments where no written procedures exist on regulation legislative actions. This is default procedure adopted in March of 2018 to allow redress to a district court.

The State of New Mexico passed HB 58 in the 2018 legislative session that also streamlines public comment for all state agencies from 60 days to 30 days, with some public commenting periods curtailed to 15 days. The Attorney General responded with a “Concise Explanatory Statement” on default procedures for the agencies and those councils, boards, and commissions who don’t have procedures in place, to submit findings of evidence-based policy decisions. Now a state agency must give findings, a reason to reject and/or accept the proposed project or legislation on a public comment submitted. Not all comments fall under one umbrella. On a quasi-legislative issue where a decision would impact citizens who are allowed a right to address grievances to the district court; and in cases at the local level, agencies, boards, county commissions, these entities must give findings on public comments where no written procedures exist on regulation legislative actions. This is default procedure adopted in March of 2018 to allow redress to a district court.

The NMENV has a couple of discharge permits that have been streamlined for discharges of fuel storage recovery remediation and bio-mediation. Various NM state agencies are in the process of writing their own agency rules for public participation are now writing public participation plans due to the new streamlining act HB58. This is particularly concerning since the release of the white paper on produced water from oil and gas production being experimented with in our aquifer storage and recovery system.

On November 9th, 2018, a draft report on produced contaminated fracking water remediation released from the NM EMNRD, outlines the MOU’s between EMNRD, the EPA, the NMENV, and NMOSE. It shows that the State and the Federal Government has had behind closed door discussions on experimenting with the groundwater and surface drinking water supply by allowing ‘Remediated Water’ into Aquifer Recovery and Storage Systems and releases to surface water without notification, public comment or hearings on the matter. This is government terrorism through state capture by industry upon the people of the state of New Mexico.

In August, representatives from more than 15 environmental and community groups signed onto a letter to the EPA, saying the agreement between the federal agency and the state violated the Federal Advisory Committee Act (FACA), which sets the rules for establishing advisory committees.

Jeremy Nichols, climate and energy program director with WildEarth Guardians, which initiated the letter to EPA, criticized the paper released last week.

“It was prepared with no public input, and it’s based on the make-believe notion that the oil and gas industry’s wastewater could somehow be put back into our water systems, including our agricultural and drinking water systems,” he said. “While it acknowledges the enormous and dangerous uncertainties associated with reuse of wastewater, including immense public health and environmental risks, the report continues to advance the myth that it may be possible for toxic fracking waste to be used for drinking water, farming or sustaining New Mexico’s fragile aquatic ecosystems.”

He credited the paper’s authors for recognizing “huge knowledge gaps in terms of health and environmental risks,” but said the paper’s “saving grace” may be that it’s coming from a lame duck administration.

To comment on the white paper through Dec. 10, people can send suggestions and input to renewablewater@state.nm.us or mail them to the Energy, Mineral, and Natural Resources Department: c/o OFS/MOU, 1220 S. St. Francis Drive, Santa Fe, NM 87501.

The white paper and additional information are online at:http://www.emnrd.state.nm.us/wastewater/index.html

Part of the fracking industry impacts is on roads and the maintenance of these roads. The Environmental Action NGO issued a report on, “The Cost of Fracking.” A community of fewer than 100,000 residents averages nearly $40M a year in road maintenance. Without notification on pending projects that would impact the lives of citizens who normally do not address state agencies, they would not know that their right to public comment and participation is currently being streamlined until a later date tried to comment on a proposed project. This is another current example of the state agency giving public notice on their website regarding public participation and public commenting process.

The New Mexico Department of Transportation is seeking public comment on its Public Involvement Plan. The 45-day public comment period will run from Oct. 29, 2018, through Dec. 13. Read the plan online and send comments to Rosa Kozub at rosa.kozub@state.nm.us

Different types of Public Commenting Procedures

It is important to understand the various types of public comments and how they apply.

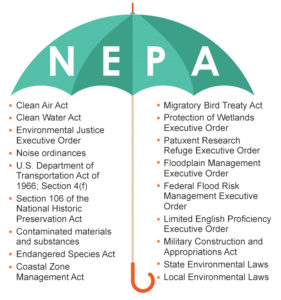

Federal and State Regulatory agencies will follow the NEPA Process

Public comment embedded in actual meetings is typical of meetings convened by legislative or executive bodies; judicial units do not have public comment, but rather testimony from witnesses and procedural  statements from attorneys. Public units such as city councils or county commission are typical examples of legislative public comment hearing bodies. Note: comments may be written, oral, or electronic but they have to set criteria at the beginning of each year, as to how they will proceed on issues that come before them and whether they are to testimony, comments and consider incorporating the comments into the proposed draft as a part of the official record of the case or agenda item being considered.

statements from attorneys. Public units such as city councils or county commission are typical examples of legislative public comment hearing bodies. Note: comments may be written, oral, or electronic but they have to set criteria at the beginning of each year, as to how they will proceed on issues that come before them and whether they are to testimony, comments and consider incorporating the comments into the proposed draft as a part of the official record of the case or agenda item being considered.

There are two types of comment periods. One is when a comment goes to a specific agenda item or project. Secondly, there is a class of public comment, which pertains to actions being taken and at what level of government is being decided. However, it is necessary that comments be restricted to matters within the jurisdiction of the government body, not on specific issues. Changing the rules in the middle of the game has repercussions. Those repercussions include a negative view of authority, lack of opportunity to participate, lack of response from officials, boards and social exclusions and ultimately lead to large populations not voting.

This latter requirement is seldom enforced except in those unusual cases in which commentators have set themselves at odds with “policy” makers and have been designated as a nuisance. “ Usually this tag is given to a group of individuals who oppose a project because they became aware of health and safety issues not being addressed. The distinction given as a “nuisance” of someone with an opposing viewpoint impinges upon free speech association of a group. Many times the ability to enter items into the record is not allowed and violates due process for redress to the district court and may be a violation of the Administrative Procedures Act. (Each state adopts the federal regulations to adhere to state law.) New Mexico just adopted their new state rules. Many areas of the agencies commenting periods at local levels only allow “qualified” public presenters, meaning industry lobbyists or representatives.

In such cases, there are usually more explicit reasons given for restricting the rights of such speakers, however, the most undesirable comments tend to be outside the scope of legislative jurisdiction.

The above distinction between agenda-item public comment and what is called “General Public Comment” pertains both to legislative type bodies as well as executive agencies. These are typically commissions, committees or boards. There are typically public comment periods during meetings of agencies such as city councils, county boards, and agencies, which are concerned with matters such as ordinances, water quality, fish and game, sewer runoff management and transportation. Time limits frequently range from one to five minutes for unscheduled presentations. It is not typical to require that the person commenting be a resident, a registered voter, a qualified elector, or even a citizen, simply that they are present and able to speak.

A whole different class of public comment is requested by agencies which are seeking input on draft policy documents such as Environmental Impact Reports (EIR), study (EIS), which provide information which may be used in policy determinations by their own agency and other agencies at various levels of government. Typically there is a notice of completion of the draft, which is posted in the newspaper, on the web, and is mailed to known interested parties who may be designated as “stakeholders” or simply “interested parties”. A public comment period is established and comments, which are received by the cutoff date, become part of the official public record. In some cases, there is a statutory mandate that those comments be replied to or incorporated in some fashion into the Final document.

At the local level that should be decided in the open meetings act resolutions or ordinances set within the first month of the year, prior to hearing any agenda items before the commission, board or agency.

In each of these proceedings, there are specific time periods and administrative procedures that are being changed including the way which the decision process is determined or outlined.

| RULE Making Process in NM

Nomenclature is utilized at the state and local level. |

||

| NPRM

Notice of Proposed Rulemaking (NPRM) NPRM procedure is required and defined by the Administrative Procedure Act. This procedure is issued first and then other procedures follow up. |

NPNM is when a public notice is issued by law when one of the independent agencies of the US government wishes to add, remove, or change a rule or regulation as part of the rulemaking process. It is an important part of United States administrative law, which facilitates government by typically creating a process of taking of public comment. | The specific criterion for state and local issues.

Many times this is adopted at the Local levels in ordinances that address regulating land use. Notification of public notice has specific criteria set by state and local law. The Constitution does not require NPRM. Rather, Congress created the requirement to enlighten agencies — that is, to force them to listen to comments and concerns of people whom the regulation will likely affect. |

| Notice of inquiry (NOI),

Pre Draft Proposal |

This is where comments are invited but no rules have yet been proposed. Comments received in this period allow the agency to better prepare the NPRM by making more-informed decisions on proposals. | Comments taken before the proposed rule are available |

| Further notice of proposed rulemaking (FNPRM), FNPRM

‘Defined after the draft proposal is advertised and additional comments can be made on changes to draft proposal. |

An NPRM may be followed by an FNPRM if the comments from the initial NPRM lead the agency to drastically change the proposal to the point where a further comment is required. Rules are finalized when a report and order (R&O) is issued, which may be amended with a second R&O (or more) in a continuing proceeding. | Once the rule is proposed, in streamline procedures this step is rarely happening because of many Findings of No Significant Impact

FONSI’s. Only in the case where significant changes and findings are made would this step be initiated. |

The Administrative Procedure Act governs the process by which federal agencies develop and issue regulations. The APA addresses other agency actions such as the issuance of policy statements, licenses, and permits. It also provides standards for judicial review if a person has been adversely affected or aggrieved by an agency action. This is why the NM Office of the Attorney General determined that findings on public comments be given by local and state agencies and why it applies. This is an important part of United States Administrative Law, which facilitates government by typically creating a process of taking of public comment.

Each notice, whether published in the Federal Register or personally served, includes:

- A statement of the time, place, and nature of the proposed rulemaking proceeding;

- A reference to the authority under which it is issued;

- A description of the subjects and issues involved or the substance and terms of the proposed regulation; VERY IMPORTANT and often time it is not part of attachments and violates the transparency that good government should be following.

- A statement of the time within which written comments must be submitted; and

- A statement of how and to what extent interested persons may participate in the proceeding.

In the ‘Guide to the Rulemaking Process,’ prepared by the office of the Federal Register, ‘The notice‐and‐comment process enables anyone to submit a comment on any part of the proposed rule. This process is not like a ballot initiative or an up‐or‐down vote in a legislature. An agency is not permitted to base its final rule on the number of comments in support of the rule over those in opposition to it. At the end of the process, the agency must base its reasoning and conclusions on the rulemaking record, consisting of the comments, scientific data, expert opinions, and facts accumulated during the pre‐rule and proposed rule stages.

To move forward with a final rule, the agency must conclude that its proposed solution will help accomplish the goals or solve the problems identified. It must also consider whether alternate solutions would be more effective or cost less.

If the rulemaking record contains persuasive new data or policy arguments or poses difficult questions or criticisms, the agency may decide to terminate the rulemaking. Or, the agency may decide to continue the rulemaking but change aspects of the rule to reflect these new issues. If the changes are major, the agency may publish a supplemental proposed rule. If the changes are minor, or a logical outgrowth of the issues and solutions discussed in the proposed rules, the agency may proceed with a final rule. All this is reduced to the decisions of the Board or agency is at the discretion of those making the decisions. This is why rules specific to how those decisions are guided need to be included in the OMA ordinances at the county or local level, or at the rulemaking procedures at the regulatory level at the Federal and State levels.

A procedure helps define and qualify processes that allow for findings and helps express why the public comments are accepted or rejected.

A quasi-legislative capacity is that in which a public administrative agency or body acts when it makes rules and regulations. When an administrative agency exercises its rule-making authority, it is said to act in a quasi-legislative manner. Administrative agencies acquire this authority to make rules and regulations that affect legal rights through statutes. This authority is an exception to the general principle that laws affecting rights should be passed only by elected lawmakers.

Administrative agency rules are made only with the permission of elected lawmakers, and elected lawmakers may strike down an administrative rule or even eliminate an agency. In this sense quasi-legislative activity occurs at the discretion of elected officials. Nevertheless, administrative agencies create and enforce many legal rules on their own; often without the advice of lawmakers, and the rules have the force of law. This means they have a binding effect on the general public.

Examples of quasi-legislative actions abound. Dozens of administrative agencies exist on the federal level, and dozens more exist on the state and local levels, and most of them have the authority to make rules that affect substantive rights. Agencies with authority over environmental matters may pass rules that restrict the rights of property owners to alter or build on their land; departments of revenue may pass rules that affect how much tax a person pays; and local housing agencies may set and enforce standards on health and safety in housing or in an oil and gas regulations that impact regional air and water quality. These are just a few of the myriad rules passed by administrative agencies.

Except where prohibited by statute or judicial precedent, the quasi-legislative activity may be challenged in a court of law. Generally, a person challenging quasi-legislative activity must wait until the rule-making process is complete and the rule or regulation is set before challenging it. Moreover, a challenge to an agency’s rule or regulation usually must be made first to the agency itself. If no satisfaction is received from the agency, the complainant can then challenge the rule or regulation in a court of law. Unlike most common-law jurisdictions, the majority of civil law jurisdictions have specialized courts or sections to deal with administrative cases, which, as a rule, will apply procedural rules specifically designed for such cases, and different from that applied in private-law proceedings, such as a contract or tort claims.

Another distinctive feature of quasi-legislative activity is the provision of notice and a hearing. When an administrative agency intends to pass or change a rule that affects substantive legal rights, it usually must provide notice of this intent and hold a public hearing. This gives members of the public a voice in the quasi-legislative activity.

What happens at the Federal level has had a trickle-down impact at the local levels where citizens have little say over quasi-judicial land use agendas and procedures that impact their public health and safety. The shorter time periods and lack of information from the local governments in a timely and outlined procedure deem to find the streamline rulemaking in favor of industry and business. If the Board is not following the APA the citizens adversely impacted do not have a standard by which they can address their grievances.

At the Local Level

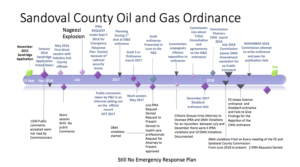

Since November of 2015, we, the individuals, citizens’ groups, NGOs, and tribal nations, have been engaged in a public participation process with Sandoval County on the six different oil and gas ordinances that have been drafted. During the Sandridge Drilling application in 2015-16, several hundred citizens (over 2500) wrote the County emails that were combined into one unscannable PDF that the County Commissioners refused to read. They indicated that it was because of the sheer volume of the response, mostly opposing the Sandridge county drilling application, that was and still is under a special use permitting.

After the Nageezi explosion in July 2016, we filed a public documents request under the Information of Public Records Act (IPRA) and the County refused the request for an emergency response plan. From this point forward in the quest for open government information and public participation from the County, we  were framed as opponents of oil and gas and a ‘nuisance’. This has resulted in the County obstructing nearly every attempt for records, stopping our ability to enter information into the public record during a public hearing and denying our ability to comment or cross-examine in a public hearing. The Sandoval County Planning & Zoning (PZ) director has a clear bias towards industry and has repeatedly made misleading remarks and given false advice to the Commission, influencing the drafting of a very bad ordinance, which streamlines and deregulates, offering little protection to humans and the environment.

were framed as opponents of oil and gas and a ‘nuisance’. This has resulted in the County obstructing nearly every attempt for records, stopping our ability to enter information into the public record during a public hearing and denying our ability to comment or cross-examine in a public hearing. The Sandoval County Planning & Zoning (PZ) director has a clear bias towards industry and has repeatedly made misleading remarks and given false advice to the Commission, influencing the drafting of a very bad ordinance, which streamlines and deregulates, offering little protection to humans and the environment.

The County has obstructed the IPRA and OMA (Open Meetings Act) Open Government laws. We have clearly documented 3 IPRA and 10 OMA violations during the 2017 ordinance process. The County brought forward the failed ‘Stoddard’ ordinance again in 2018 as the Baseline Ordinance, after throwing a 25-member chartered Citizens Working Groups Chartered committee under the bus along with their CWG land use ordinance. Instead, Commissioners inserted some of the CWG land use provisions, only to hatchet them later from the ordinance. They were interested in the CWG Science ordinance that was to ban fracking in the immediate Rio Grande Sub-basin but still allowed conventional drilling. They also made last-minute insertions of 6 square miles to be exempted from the ban fracking zones in the Rio Rancho Estates. They did this without advertising maps or defining for the public where and what those areas are, did not advertise a closed meeting on their website prior to the ordinance consideration, and they never formally adjourned the meeting. The only pool of oil in the basin available is under the Rio Grande. Banning fracking in one area increases the burden on Pueblo, Dine’ and Hispanic communities already experiencing respiratory illnesses in the Northwest part of the County.

Each year the County adopts an Open Meeting Act Resolution to follow through the course of the year. The County has never changed that but in July of this year, they disallowed public comment until the final approval of the O&G ordinance. In September 2018, the County proposed another amendment to OMA to violate the free speech and the free association of employees and elected officials. We were able to defeat their violation of free speech on this OMA amendment. The County did not allow any of the ordinances while in the PZ procedure to go for a public comment until the final approval when they abdicated their responsibility and tossed an incomplete ordinance back the County Commission. As stated prior to the Sandridge application procedures the majority of PZ and county commissioners did not read email comments.

They have suggested once again to send the public comment through their website in 2018. However, this is not a public hearing and it is not required that they accept the public comments into the record. Therefore, the public comments are not a part of the official record. This is important because as stated prior (this is an excerpt from a large report) the County defaults on the quasi-legislative ruling making procedures when citizens have the right to redress their grievances in district court.

The County has not given findings on why they have accepted or rejected the Public comments they received or why they ignored the Citizens Working Group ordinance that attempted to address land use concerns.

The Citizens of Sandoval County have been harmed by the governance from the County Commission on the free speech, open government, and transparency laws that are supposed to shine a light on the records which give citizens the understanding of the issues before them. Instead, people with opposing viewpoints or even suggestions for the Commission to consider are treated as nuisances with threats of arrest after they refuse to hear people and only to have squashed their voices from the official record. They are not allowed to address the substantive issues they are entitled to under the law in comments of one or two minutes. Under Roberts Rules of Order cross-examination is allowed but the chairman will not allow it.

From January through May 2018, our group tried to form a Local Emergency Response Planning (LERC) Committee, insert language into the ordinances, and bring up the conflicts of interest that need to be addressed before the public. The County has a fiscal interest in fracking and selling water to fracking operations. All attempts to participate were thwarted, ignored or met with threats of arrest when trying to state the issue in a 1, 2 or 3-minute time frame with no opportunity for presentation and discussion on concerns that need to be on the record. Usually, this happened in a public hearing when Robert’s Rules of order is followed because it gives the opportunity for redress of both sides. The Commission will not allow the rules of order to be implemented.

As a result of following the meetings, we worked to document further violations of the Open Meeting Act (OMA) and Inspections of Public Records Act (IPRA). We have had to file a complaint with OAG on every meeting, which there was an infraction of the law under OMA and the Administrative Procedures Act (APA) state laws.

The Office of the Attorney General (OAG) is investigating the complaints filed but the office is 6 months behind on the complaints. The OAG rarely enforces the law on IPRA and OMA, but rather punts the question back to the complainant to find remedies in District Court. This is how rogue commissions like Sandoval County’s are allowed to violate the law and put industry profits over the needs of the people.

Without enforcement of the law, there is no rule of law. As Sandoval County citizens and New Mexicans, we are living in a “State Capture” society, where regulations and laws are being implemented that disproportionately support industry profit and legitimize corruption.

The definition for State Capture is as follows:

“State Capture” is defined as the efforts of individuals or firms to shape the formation of laws, policies, and regulations of the state to their own advantage by providing illicit private gains to public officials. The key distinction in this typology is not, for example, the size of a bribe nor the level in the political system where bribery occurs, but rather whether the corruption is directed to distort the intended implementation of laws or to shape the formation of the laws themselves.

The NM state agencies that oversee the oil and gas industry are run by former petroleum company CEO’s and lobbyists. Add in dark money campaign contributions like the $2M donation to Governor Martinez’s campaign and pay-to-play corrupt activities in both parties, and its unsurprising that the industry essentially controls the agencies (like the OCD and NM-EMNRD) that oversee it. Now they are doing the same for the State Land Commissioner race in 2018. Even the ballot initiative for an NM constitutional amendment of an ethics commission, sorely needed and sure to pass, will have little impact on this problem because it has no subpoena power, no commission while not in session, no budget, and meets in closed sessions.

Why citizens do not participate in the governmental process.

- A Negative View for authority

- Lack of opportunities to participate

- Lack of Council or Commission Response

- Issues of Social Exclusion

Why do citizens participate in government?

A range of interacting motivations for participation.

It challenges the idea that the public is universally apathetic and throws light upon current deterrents to participation in local government. The research findings point to the potential value of local authority strategies which:

- Ground consultation in good ‘customer care’.

- Address the stated priorities of local residents and involve all relevant agencies.

- Mobilize and work through local leaders (informal as well as formal).

- Invite or actively recruit participants, rather than waiting for citizens

to come forward.

- Employ a repertoire of methods to reach different citizen groups and

address different issues.

- Recognize citizen learning as a valid outcome of participation.

- Show results – by linking participation initiatives to decision-making,

and keeping citizens informed of outcomes (and the reasons behind

final decisions that are given with findings on public comments and through appropriate governmental communications.

What does good open government look like?

Open government has many definitions. By articulating transparency, social participation, accountability and technological innovation, this concept and its practice has been increasingly prominent in the public policy agenda. The richness of interpretations can generate expectations and frustrations among those who participate in open government processes and distance those who might be involved in these processes. This is because of different areas of how cultural knowledge address it, different actors and political and cultural contexts. This is why it is important to ask: what is an open government? What are the principles of open government?

From the point of view of the main institutions that deal with this subject, open government is mainly linked to the promotion of transparency policies and their related themes, as well as the participation of society in the public policy cycle. In this perspective, for some actors, it is fundamental to emphasize accountability and fighting corruption as structural axes and, in general, technological innovation as transversal to other policies. This data collection can be seen in Table 1 of the research* “What is the concept of Open Government? An approach to its principles“, which seeks to draw new perspectives for this agenda.

However, there are cross-cutting themes of major importance that are not clearly included in these definitions of open government, such as gender, diversity, inclusion, language, and accessibility. The inclusion of these themes would allow a better dialogue with the goals of the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGS or 2030 Agenda) and with international declarations on women’s rights, minorities, and human rights standards. In addition, we believe it is necessary to conceptualize social participation, to include open data as a basic component, and to assume collaboration and co-creation as a method for the construction of open governments.

Briefly, we propose here a set of guiding principles of a clearer and more objective concept of open government, at the same time as comprehensive and inclusive. The idea is that they can serve as a reference for governments, civil society, the private sector, and international agencies to discuss and elaborate their policies.

| Principle | Proposed Principles for Open Government

Description |

| 1. Effective participation | Participation is encouraged and includes informing, consulting, involving and empowering citizens and social organizations. |

| 2. Transparency and accountability | Governments must actively account for all their actions and take public responsibility for their actions and decisions. |

| 3. Open Data | Open, complete, primary, timely, accessible, machine processable, non-discriminatory, non-proprietary, license-free data must be made available and in accordance with international standards for publishing data on the Web. And the security of Data Collection because of lost public comments at the BLM on oil and gas lease sales. |

| 4. Opening and reusing public information | Public information must circulate to reach its full potential. Priority is given to the use of license-free, allowing the reuse of information. |

| 5. Access and simplicity | Whenever possible, simple and easy-to-understand language is used. |

| 6. Collaboration and co-creation. | Practices and policies are designed to encourage collaboration and co-creation at all stages of the process. |

| 7. Inclusion and diversity | There is attention to diversity and inclusion. Women, the disabled, minorities and/or vulnerable are included. Attention includes the use of appropriate languages, technologies, and methodologies to include minorities. |

End Notes:

Changing the rules in mid-stream Ann Maria Island Sun May 1, 2017 https://www.amisun.com/2017/05/01/changing-rules-mid-stream/

How the Public Is Losing Its Voice on Public Lands Ben Goldfarb September 20, 2018 https://www.audubon.org/news/how-public-losing-its-voice-public-lands

The RAPID Act: the latest attack of NEPA https://www.nrdc.org/experts/amanda-jahshan/rapid-act-latest-attack-nepa

EPA, state agencies want public input on drilling wastewater report By Laura Paskus

Transparency concerns about oilfield water reuse plans met with silence By Laura Paskus

Congressional Record at https://www.congress.gov/bill/114th-congress/house-bill/348/text HR 348

The Streamlining act and other development time limits http://www.cacities.org/UploadedFiles/LeagueInternet/c1/c1174374-f6b2-4723-af76-b0d8ddcc60e0.pdf

The Administrative Procedures Act (APA)5 USC §551 et seq. (1946) https://www.epa.gov/laws-regulations/summary-administrative-procedure-act

NM rulemaking APA

http://www.nmcpr.state.nm.us/nmac/parts/title20/20.001.0001.htm

A Guide to the Rulemaking Process Office of the Federal Register https://www.federalregister.gov/uploads/2011/01/the_rulemaking_process.pdf

Quasi-legislative capacity